|

Awareness of divinity

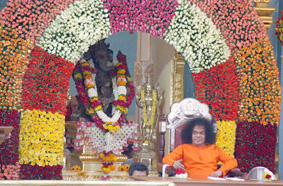

Sathya Sai exudes a rare grace that

captivates seekers of truth

By Bill Aitken

Any attempt at summing up the contribution of God-men to

society—in modern India’s English media—is fraught with the prospect

of either audience fatigue or cynicism, especially when the subject

is Sri Sathya Sai Baba, an essentially vernacular figure (his

biodata is available only through translation from Telugu). As a

result, the views about Sai Baba’s place in the history of religion

veer from one extreme to another. While one faction has a mass

regard for him as the Godhead, the other crusading minority clamours

through the sensational press to have his standing reduced to that

of a common fraud.

Obviously it is only from the middle ground, examined by

objective, inquiring students of religion that Sai Baba’s status can

be expected to emerge. But such neutral observers are thin on the

ground. Having been a critic myself (of Sai Baba’s apparently

inflated spiritual claims), I have found on closer examination over

the years that my initial reaction was fairly normal and actually

welcomed by Baba.

I have been forced to revise my opinion and accept that this

person does not say he is divine to the exclusion of others. What he

says is that everyone of us has divinity within ourselves. He,

however, unlike the rest of us, is fully aware of this truth. It is

this sense of abiding awareness that many seekers (as opposed to

casual visitors) experience in his presence that sets this teacher

apart and makes him like no other spiritual phenomenon that I have

ever read about or personally checked out in the 50 years that I

have studied comparative religion.

The theological contribution of

the Sai saints has been to emphasise the equality of souls before

God. The theological contribution of

the Sai saints has been to emphasise the equality of souls before

God.

The critical factor for determining his unusual spiritual aura,

oddly enough, is crystallised by the darshan of his slight but

remarkable physical presence. Sathya Sai exudes a rare grace that

captivates any seeker who is after the real things the human soul

hankers for. Between the hype of unhinged devotees and a howling

pack of detractors, his diminutive figure appears the same today as

it was when he was a boy—serenely established in a mood of

unaffected humaneness. When asked how his students should dress,

Baba replied with a subtle rebuke to today’s fashion of unconcern

for other’s problems: "Dress in such a manner that no poor person in

need of assistance will hesitate to ask you for help."

The category of divine is impossible to qualify but people rich

and poor, from all walks of life and different continents, confess

that in the presence of this unlikely fuzzy-haired Andhra peasant

they experience a grace that is like no other. Magically, it gives

rise to an awareness within the beholder that he or she too

possesses this priceless pearl of selfhood.

Sathya Sai is the occasion and trigger of this other-worldly

experience. His being is a reflection of the truth. This reality,

which he embodies momentarily, is awakened in the seeker. Unless you

savour this moment of grace, no amount of reasoning is going to take

you nearer to the meaning of life and understanding of the

pre-eminence of love. We are born to find this liberating truth in

ourselves. (Finding fault in others is not so urgent!)

This altogether mystifying personage, now celebrating his 80th

birthday, is strangely untouched by his outer state of rags to

spiritual riches story, and his inner state remains imponderable to

all, except, crucially, to himself. Inevitably, most intellectuals

who seek wisdom will shy away from the surrender of their shining

minds, especially before a backward villager. Custom dictates that

knowledge is power and the aim of life for most is to seek the polar

opposite of love. The few (of all nations and conditions) who do

foregather in Puttaparthi to celebrate the paramountcy of love are

at one with their teacher and themselves. The observer gets the

distinct feeling that the Bodhisattva or avatar (or any exemplar of

human compassion like Sathya Sai) is the goal of human evolution.

The greatest miracle on show at Puttaparthi is to witness this

humble villager’s natural graces daily, which far exceed those of

the so-called "most powerful man in the world" in Washington.

The theological contribution of the Sai saints has been to

emphasise the equality of souls before God. This theistic approach

contradicts the paramountcy claimed by Sankaracharya for advaidic

monism. Historically, south India has led the north in shedding the

fatalistic notion that birth of the body decides the destiny of the

soul. Both Sai Baba of Shirdi and Sathya Sai Baba of Puttaparthi

have been revolutionary in preaching and practising spiritual

egalitarianism, which is particularly relevant to India’s democratic

policy still mired in a feudal mindset. It is significant that both

Sai Babas have emerged from the Deccan where Dravidian influences

mingle with the Brahminical, Islamic, Christian, Sikh and Humanist.

For the student of subcontinental religious affairs it is

fascinating to watch the cultural arm-wrestling as Shirdi Sai,

originally presented as an anonymous Sufi in torn white kafni, is

nowadays sought to be passed off as a sanyasi in saffron with a

Brahmin pedigree.

Having watched Baba for more than 30 years I have moved from my

original position of intellectual doubter to that of a fascinated

observer. I find he is a worthy understudy of Shirdi Sai and in my

own pantheon of great beings, he finds a place alongside the Buddha

and Christ.

Recently, Marianne Warren published her Ph.D thesis, Unravelling

the Enigma, arguing that since Shirdi Baba was a Sufi, Sathya Sai’s

claims to be an incarnation of him are totally misplaced. This

illustrates the limitations of the intellect and how the

presumptuousness of scholars blinds them to the obvious fact that

the mystery of rebirth is not open to proof one way or the other. As

in all religious affairs, these things are personal matters and

historicity is not as important to the heart as the feeling of

oneness the two Sai masters engender. When truly in love the

analytical mind is in abeyance.

The controversy over Sathya Sai’s status has thrown up elements

of the ridiculous at both extremes. His basic followers, Telugu

farmers in the early days of his mission, sought to see miracles in

everything the boy saint did. Chain letters were sent to stoke the

impression of a cult of unbalanced believers, totally at odds with

the teachings of Sai Baba—that you must weigh the evidence of a

teacher’s spiritual worth before taking the plunge of faith to win

his protective aura. When Professor Kasturi penned the official life

of Sathya Sai (as the perceived avatar of Lord Shiva and Parvati),

it was directed at a devotional, rustic audience. For the rational

reader, the most authentic biography of Sathya Sai in English has

been written by Howard Murphet, an Australian.

The exponential growth of the Sai mission after his sole foreign

trip to Uganda in 1968 saw a huge influx of overseas interest and

funds. The dramatic expansion of the Prasanthi Nilayam ashram—with

an international-class hospital, a deemed university and massive

outlay of drinking water schemes for the drought-prone Rayalaseema

district—helped the world to distinguish the universal compassionate

nature of Baba from his earlier image of a miracle-mongering yogi.

His unique, unchanging persona and the dynamic harnessing of

goodwill that he arouses for social improvement make him much more

than a conventional fund-raising mahatma. He is one of the few

compassionate beings rarely seen on earth, concerned solely for the

advancement of the human spirit.

Sai Baba's concern for quality

education and medicare is a positive input for nation

building.

At the other end of the spectrum is the

violently vociferous lobby of local rationalists (convinced that Sai

Baba is a confidence trickster) and international apostate disciples

(who paint Sai Baba as the Anti-Christ). To add to the chagrin of

these voluble detractors, who have criticised his career in print

and on the Internet with malicious intensity for at least a

generation, is the ongoing booming growth of his mission. The more

they rail against the saint, the greater, it seems, is the number of

people who flock to have his darshan.

The critics are so intemperate in their

dislike that their vituperation now comes across as almost near

comical in its predictability. Nothing Baba can say or do meets

their approval. If he provides drinking water to thirsty villagers

they scent a scam but if he doesn’t provide drinking water he is

anti-poor. The ground reality is that even Naxalites have welcomed

Baba’s charitable intervention, recognising in him a fellow son of

the Andhra soil. Often the impression given is that the vilifiers do

not hate Sai Baba as much as they harbour contempt for the religious

feelings of ordinary cultivators, whose devotion has made Sathya Sai

what he is.

Probably because of the intensity of

their hate, when it comes to a serious, forensic examination of

their allegations, they resort to bluster and evasion instead of

hard facts. Smearing sexual innuendo is a traditional ploy but on

failing to substantiate their charges, the critics switch to another

unrelated subject.

They will claim that all of Sathya Sai Baba’s materialisations

are phoney. However, this cannot stick either, because millions have

witnessed the outpouring of vibhuti at Shivaratri. So then,

financial irregularities are imputed to the saint, and when these

are likewise found to be unproductive of scandal, mafia happenings

are invoked. (As a longtime observer of ashrams, I always note how

Puttaparthi is exceptional in not making any monetary demands on the

visitor.)

The strategy of the critics seems to be that if sufficient mud is

thrown, some might stick. This hit and run behaviour suggests a

neurotic concern to damn by any possible means. Certain foreign

evangelical missions invest in these hate campaigns as a godly task

while in international forums, pressure on voting patterns is

discreetly applied by lobbyists of rival religions, to further their

own cause.

The latest in these so called exposes is a BBC documentary whose

agenda was so predetermined to denigrate Baba that it stooped to the

unethical use of a spy camera. In a last farcical gesture, the

producer hired some roadside entertainers to attempt to simulate

Baba’s chamatkar. The result is so ludicrous that it leaves the

viewer wondering as to who is funding this bizarre display of

hostile reporting. The BBC is ultimately governed by the Anglican

establishment, and churches in the west are losing out financially

to the appeal of the Sai Baba movement.

As a commercial broadcaster, the BBC’s

opting for sleaze would have the dual advantage of discrediting a

rival as well as getting good audience rating. The Church of England

can have no objection to programmes that weaken perceived

threats—like the papacy or Hindu holy men—to its (declining)

influence in the world. Posing as a lion in Asia, the BBC is a mouse

in Britain. It dare not criticise public icons like the Queen, who

happens to be the supremo of the Anglican church.

Even negative assessments of the Sai

movement have to concede that its growth has been phenomenal and

that, remarkably, there has been no missionary effort involved. It

has increased by spontaneous identification, where individuals have

been drawn to the persona and teachings of the Sai saints, a

voluntary outpouring of faith that has occurred in an amazingly

short period.

In appealing to the core of spirit that

lies beneath the surface of all religions, the Deccan saints have

not only made a dent in the fragmentary nature of the subcontinental

religious loyalties but also restored the classical Upanishadic

insight of the oneness of all faiths.

This augurs well with the Indian

democracy’s need to get beyond religious labels that have stultified

its development since Independence. Baba’s concern for quality

education and medical care is another positive input for nation

building. The success of his peninsula drinking water network has

proved that for efficient development, the crucial ingredient is

sincerity of purpose.

Bill Aitken is an expert on comparative

religion and a travel writer. He is author of Sri Sathya Sai Baba: A

Life.

Puttaparthi

By N. Bhanutej

Traversing rocky mountains and never-ending plains to reach

Puttaparthi, one does not expect gigantic film set-like buildings in

this back of beyond. Bordering on the gaudy, the buildings—the

hospital, the music academy, the university, etc.—painted mostly in

pink, have a stamp of Sathya Sai institutions on them. Even the

police station and the bus stand have temple

architecture.

Puttaparthi's economy is booming. Crises like drought or stock

melt-downs don't seem to affect this over-grown village. Puttaparthi

comes to a halt only when Baba moves to his ashram in Bangalore.

Every business establishment here displays a picture of Baba

prominently. Every establishment has 'Sai' in its name. Even to get

a waiter's attention in a restaurant, one has to shout 'Sai Ram'.

Beggars on the street call out 'Sai Ram' to passers-by.

On the main streets, there is a significant number of foreigners.

The economy revolves around these dollar-rich visitors. There are

also several Kashmiris, who sell carpets and other handicrafts to

foreigners.

Some shops exclusively sell pictures of Sai Baba. Said one

shopkeeper: "Ash could start falling from one of these pictures if

you are lucky."

Puttaparthi is completely vegetarian. Though not official, there

is a ban on liquor. Young boys in white are a common sight here.

They are students of one of the many colleges run by the Sathya Sai

Central Trust. When asked what he wanted to become, a boy, who is

doing B.Com., said: "I want to do MBA from our institution. Swami

will guide me on what to become."

Would he join a new-age company as an executive? "I am blessed if

Swami asks me to manage one of his institutions," he replied.

Students of institutions managed by the trust are forbidden from

speaking to the media, he said.

Counterpoint Counterpoint

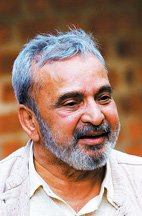

By U.R. Ananthamurthy

Although I grew up in an orthodox family, I questioned many of

our traditional notions, particularly the caste system. Hence, I had

difficulty in following a religious leader. I remember my parents

paying respects to Sai Baba when they were unhappy. Since I loved

them, I never criticised such things vehemently.

But it was funny to see people getting rings and vibhuti from Sai

Baba. It is cheap to make people believe in God through tricks. To

believe in a phenomenon like Sai Baba is like losing my spiritual

awareness. My friend's wife refused to undergo surgery for

breast cancer on Baba's assurance that she would be cured. She died

without an operation. It is wrong to advocate such belief systems

because all of us will die. We must realise this truth.

Once at the Hyderabad airport, Kannada writer Prof. V.K. Gokak,

who worked with Sai Baba, was waiting for him on the flight I was

on. Another well-known Kannada writer, V. Seetharamaiah, a

traditional man with petha [turban], was sitting next to me. "What

is happening?" I asked him. "The flight is delayed as they are

waiting for Sai Baba," he said.

Once Baba arrived, the crew and passengers, mostly

vice-chancellors of prominent universities, bowed to Sai Baba and

got vibhuti from him. "Why don't you go, sir?" I asked

Seetharamaiah. "I'm an old-timer," he replied. Real old-timers

didn't need a Sai Baba.

I cannot understand how people are not sceptical about Sai Baba.

One of the great Indian traditions is scepticism. Without this,

Buddhism, Jainism and Veerashaivism would not have been born.

India's true spirituality can be found in people like Kabir, Basava,

Tukaram, Ramakrishna Paramahamsa and Ramana Maharishi. I don't know

how to fit Sai Baba in that list. Between Sri Sri Ravishankar [Art

of Living Foundation] and Sai Baba, Sai Baba is better because he is

more easily available to the ordinary people.

I recently watched Sai Baba on television and he looked old and

sick. But there is kindness in his eyes. Many people are overcome

with emotion when they meet Sai Baba. But that magnetism is not

spiritual. People go to him for solace. Spiritualism is not solace

but to seek truth, which is harder. Spiritualism requires a kind of

mind like Jiddu Krishnamurti. I could argue with him. With Sai Baba,

either you believe him or you don't.

The 20th century is remarkable for three phenomena—hunger for

social justice, hunger for spirituality and hunger for modernity.

All the three went together. Mahatma Gandhi fought for social

justice and tried to get out of the caste system. The spiritual

streak in Gandhi emerged when he said 'Hey Ram' after he was shot

at. Today, hunger for spiritualism has given rise to commercial

gurus. Hunger of equality has degenerated into Lalu Prasad Yadav.

Modernity has become globalisation.

This is going to increase because of increasing rootlesness and a

loss of a sense of community. I have no problem with a religious

festival or even people taking the Ayyappa pilgrimage. Among Ayyappa

devotees, there is a sense of community and equality. The problem is

the hunger for persons like Baba.

What puzzles me is that he claims to be God and I laugh at him.

People also laughed at Lord Krishna when he claimed he was God. I

used to wonder if Sai Baba is also God, and if we are refusing to

acknowledge it.

I like certain things about Sai Baba. When BJP leader L.K. Advani

went on a ratha yatra, Sai Baba is believed to have said, why build

Ram temple at Ayodhya when he is present everywhere. I appreciate

his drinking water and health care initiatives. One more thing I

like about him is that he is not an English-speaking person.

The land that gave birth to great people like Gandhi and Ramana

deserves better.

As told to Rajesh Parishwad

The writer is a well-known Kannada

writer and Jnanpith award winner.

| Who next?

Waiting for Prema Sai

By N. Bhanutej

Asking about Baba's health can ruffle feathers at

Prashanthi Nilayam. Especially if the question comes from a

journalist. The secretary of the Sai Baba Central Trust

refused an interview. A request for an interview with Baba was

dismissed without a second thought.

Information on his health comes 'off the record'. An

inner-circle devotee, who did not want to be named, said that

Baba was using a wheelchair ever since his thigh bone

fractured in a fall in 2003. Surgery had not succeeded because

of "rejection", he said. The devotee quickly added that as Sai

Baba rarely travelled, the injury had not affected his

routine. "In fact, all those who have been saying that the

swami's health is failing are taking sick leave. He is as

active as ever. He has not missed a single appointment," he

said.

Decades ago, Sai Baba said that he would "leave his present

body" in 2022; that he would be reborn as Prema Sai Baba, in

Mandya district in Karnataka. In July 1975, a boy, Sai

Krishna, of Pandavapura in Mandya claimed to be Baba's next

avatar. A fact-finding committee set up by the late H.

Narasimhaiah, who was vice-chancellor of Bangalore University,

proved that the 'holy ash' produced by Sai Krishna was hidden

in the boy's vest, and that the pulling of a string delivered

it to his palm.

The organisation dismisses questions on who would succeed

Sai Baba thus: "How can anyone succeed God? Baba is for ever."

Said a member of the trust: "What is happening in Shirdi?

Everything is continuing even after Shirdi Sai Baba. Here,

too, it will go on like that."

"Who can replace God? Baba was, is and shall be," said

Baba's nephew R.J. Ratnakar. Would a certain Prema Sai Baba of

Mandya inherit the empire? "That is not known to us," said

Ratnakar. "It is known only to him [Baba]. It will happen if

he has said so. How that will be revealed, only time will

tell." |

|